This post was originally posted on Medium on May 14, 2020.

Our fingers are pointed in the wrong way at how our cities are responding to the COVID-19 crisis around the world. We constantly see on the news — our city does this but another city is praised for taking better action, or we languish at what the White House has done unsuccessfully while praising the governments of other countries that have seemingly put their populace under corona control.

While the relationship between policy and infection rates can be narrowly correlated in a simple worldview, there are so many overlooked variables that likely contribute to the relationship between infection rates and policymaking. I believe that a country’s coronavirus fate outside of policy is based on whether its major urban centers have free-flowing ties to the global economy and whether it has a populace that is adaptive to change and at least somewhat trustful of their governments.

Myth: Densely over-populated cities all around the world are teeming with coronavirus risk. Social distancing policies need to suppress the density problem.

Myth, Taken Down + Adjusted: Global cities with strong global economic ties, on top of free-flowing transportation infrastructure, teem with coronavirus risk. Social distancing policies can only be successful in these places when its wide-ranging commerce and transport is restricted.

“There is a density level in New York City that is wholly inappropriate…This is just a mistake! It is a mistake! It is insensitive. It is arrogant. It is self-destructive. It’s disrespectful to other people and it has to stop and it has to stop now. This is not a joke and I am not kidding.”

— Governor Cuomo, March 22, 2020

New York City politicians need to stop putting singular blame on its own iconic density as a tantamount reason for its explosion in coronavirus cases, and instead should retroactively blame its airports and the FAA for keeping its global contamination firehose wide open in the beginning of the coronavirus’ onset. For instance, if we know that international flights were the first initial cause of the virus’ spread (and international zones are a likely cause for secondary outbreaks in South Korea and China), we could hypothesize that high global air traffic reach, NOT urban density, is a stronger contributing factor of the high coronavirus counts now seen in the most notorious major urban centers. For example, here’s some data that compares major cities not just by their density and number of coronavirus cases, but also the global connectivity of their airports’ infrastructure along with numbers of international traffic:

New York City: 184,000+ cases, 38,242/km2 density

- New York JFK, 33,506,419 intl pax (2018), ’19 megahub index* = 186

- Newark EWR, 14,141,299 intl pax (2018), ’19 megahub index* = 169

Mexico City: 8,705+ cases, 31,598/km2 density

- Mexico City MEX, 17,204,824 intl pax (2018), ’19 megahub index* = 191

London: 18,000+ cases, 5,666/km2 density

- London LHR: ~75,300,000 intl pax (2018), ’19 megahub index* = 317

Tokyo: 4,810+ cases, 6,158/km2 density

- Tokyo NRT: 17,365,312 intl pax (2018), ’19 megahub index* = 128

*The OAG generates an index comparing number of scheduled connections to/from international flights with number of destinations served from airport.

New York City and Mexico City comprise of similar urban densities, but report drastically different numbers of cases. New York’s major international airports trump Mexico City in terms of global connectivity, which probably allowed the virus to enter the city from major infection origin points like East Asia and Continental Europe. Furthermore, while Tokyo has a greater urban density than London, London overwhelms Tokyo in its global connectivity index score, also enabling global travelers to transmit the disease into the UK from all potential early sources of initial geographic origin.

Therefore, well-connected cities that are tightly threaded to the global economy and have free-flowing public transport are liking having it worse with COVID-19 than those who are not. In both New York City and London, the dearth of 24/7 public transportation options to multiple urban airports most certainly didn’t help prevent asymptomatic individuals from traveling through central urban cores. By comparison, San Francisco and Sydney, also global powerhouses with well-connected airports, do not have the broad public transport coverage that is the hallmark of NYC and London’s global connectivity, and are not so 24/7.

So now that most international flights have slowed down, why does this observation even matter? Though we’re long gone from the initial days of the first wave, the same cities under initial risk should consider themselves as strong candidates for a relapse of the second wave of coronavirus. They should look to Seoul’s example, and stop the spread from the source — foreign nationals with long-term visas without a place of residence or on a short-term visit have been required to be quarantined at a government-run facility, at their own expense (~$100/day). We should have known better to think about what happened in the Adriatic back in 1377, when 40 day isolation periods (quaranta) were implemented for visitors coming from areas suffering from the Black Death.

Next Myth: Social distancing restrictions in the developed world are the only major way to handle further outbreak of the coronavirus.

Myth, Adjusted: Social distancing restrictions are only strongly successful in democratic societies with an adaptive populace willing to sacrifice some individualism in trusted communities.

Let’s be clear and align with the scientific experts — social distancing enacted globally has indeed slowed down overall infection rates. However, in the United States, we are beginning to see these policies fall apart as social backlash to the “repressive” rules and regulations begin to grow. Meanwhile, Sweden seems to be on the opposite end of the social spectrum, relying heavily on responsible societal values and causing its Scandinavian neighbors to doubt whether the strategy will pay off.

South Korea, the media poster child of coronavirus mitigation, has been praised for its swift reaction, high levels of testing, and a belief that its collectivist society has stomped the disease, even when the country experienced a recent second wave rebound alongside Germany. However, even highly-individualistic APAC neighbors with lower per capita testing, like New Zealand and Australia, have essentially declared the virus conquered and have opened up their societies. To my earlier point about transportation connectivity, these island nations can and have easily turned down the spigot of virus spread to a trickle at their international airports and borders, which are more importantly only dominated by a few points of entry (South Korea is effectively an island since its international airports are the predominant way in and out of the country, given its heavily-fortified land border). The social distancing policies these nations enacted were only one piece of their puzzle that has been currently solved, for now.

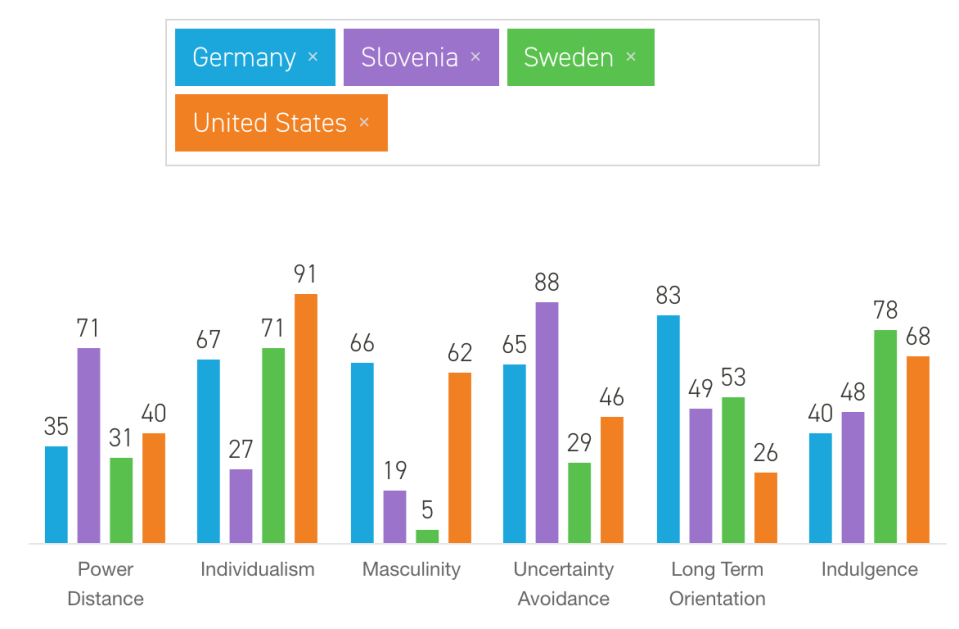

Subtracting countries which are societal islands, therefore (ex., Singapore, Japan, etc.), and being agnostic to social distancing policies, what are the common traits of democratic and globally-open countries that have squashed the initial round of coronavirus? When we look at Hofstede’s cultural dimension theory models between “success story” countries like Germany, Slovenia and Sweden vs. the United States, differences in individualism and long-term orientation stand out.

For example, while Sweden and Germany are still relatively independently-minded nations, even when compared to their European neighbor Slovenia, the United States trumps the individualism score (no pun intended), which certainly explains some of the violence and tension in the country demanding that Americans (corrected: “I”) return to work.

Long-term orientation scores, meanwhile, show the opposite results. The United States, with its significantly lower scores than Germany, Slovenia and Sweden, is a more normative society where people, according to Hofstede Insights, “prefer to maintain time-honoured traditions and norms while viewing societal change with suspicion.” This contrasts with more pragmatic societies that have a higher score; these countries “encourage thrift and efforts in modern education as a way to prepare for the future.” It’s certainly an ironic conclusion for the United States, given that it’s more typically known for its entrepreneurial push for change.

Aside from taking societal learnings from countries that have been successful, we also know what many unsuccessful countries share in common where social distancing policies have done little to curb coronavirus spread: mistrusted governments. In a Demos political poll of Italy, more than 93% of Italians said that they do not trust their own parliament. Furthermore, in Latin America, a region where the crisis continues to get worse, we know that many of its citizens are deeply distrustful of their communities:

According to a poll by Latinobarometro, 43 percent of Mexicans say they have low trust in people of their own communities. That number is 54 percent for Peruvians. In Brazil, it’s 63 percent. In contrast, in the United States only 20 percent expressed low levels of trust in people of their communities.”

— Inter-American Development Bank

In conclusion, politicians need to continue the focus on their globally-minded transport connections as well as the cultural nuances of their own local societies to determine whether or not coronavirus social distancing practices are the key tool to reduce the spread of the virus. To me, the coronavirus is a massive show-and-tell of how differently structured societies and cultures are handling an invisible enemy, where the growth rate of cases is a narrowly-focused measure by which countries validate societal restrictions. Social distancing policies will not make or break this disease — societies will.